Last year I got into using Letterboxd, to complement my goal of watching more (good) movies[1]. It’s got a really clean interface, the social features are useful but unobtrusive, and it makes remembering what I’ve watched and when I watched it easy. So why isn’t there a Letterboxd for books?

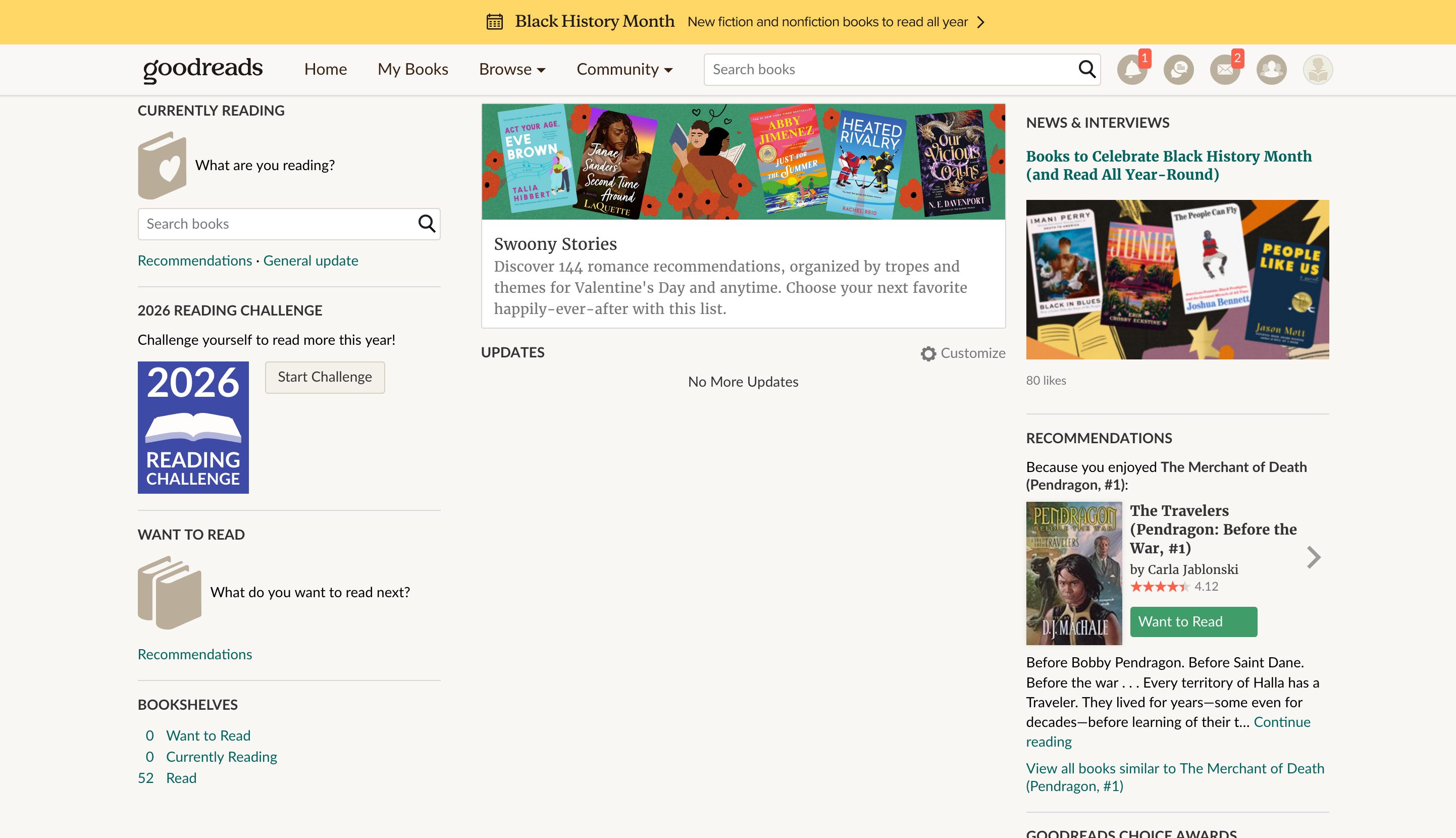

Funnily enough, Letterboxd still describes itself as “like GoodReads for movies”. But GoodReads itself is a mess. Take this screenshot of my childhood GoodReads account as an example:

Where do I log and review a book I’ve read? (The searchbar, but it takes half a dozen clicks and involves up to three different ways to log something). Where can I see the list of books I have read so I can recommend one to a friend? Where can I find books I plan to read? (Both under “My Books”, which by default shows them inter-mixed). Why is so much of the UI taken up with stuff like reading challenges and newsletters?[2] Storygraph, leading independent alternative to GoodReads, has similar problems[3]. These interfaces don’t lead me to log books; instead I just have some files in Obsidian that I sometimes remember to update.

Search

So let’s build our own GoodReads, with a UI that’s convenient enough to actually use. First we gotta build a search function for books. Then–

Wait, a search function for books. How do we do that? Well there’s the Google Books API, and it’s free which is nice. But when I search for “The Last Unicorn” (and do a little munging of the contents with jq):

$ curl -X GET 'https://www.googleapis.com/books/v1/volumes?q=The+Last+Unicorn' | jq ".items | .[] | .volumeInfo | {title: .title, authors: .authors, isbns: .industryIdentifiers | map(.identifier) }"I get this mess:

{

"title": "The Last Unicorn",

"authors": [

"Peter S. Beagle"

],

"isbns": [

"9780451450524",

"0451450523"

]

}

{

"title": "The Last Unicorn",

"authors": [

"Peter S. Beagle"

],

"isbns": [

"1417644931",

"9781417644933"

]

}

{

"title": "The Last Unicorn",

"authors": [

"Peter S. Beagle"

],

"isbns": [

"9780593547342",

"0593547349"

]

}

{

"title": "The Last Unicorn",

"authors": [

"Peter S. Beagle"

],

"isbns": [

"0345028929",

"9780345028921"

]

}

{

"title": "The Last Unicorn",

"authors": [

"Jane Elizabeth Cammack"

],

"isbns": [

"8853010932",

"9788853010933"

]

}

{

"title": "The Last Unicorn",

"authors": [

"Peter S. Beagle"

],

"isbns": [

"1596060832",

"9781596060838"

]

}

{

"title": "Last Unicorn",

"authors": [

"Peter S. Beagle"

],

"isbns": [

"1399606972",

"9781399606974"

]

}

{

"title": "Peter S. Beagle's “The Last Unicorn”",

"authors": [

"Timothy S. Miller"

],

"isbns": [

"9783031534256",

"3031534255"

]

}

{

"title": "The Last Unicorn the Lost Journey",

"authors": [

"Peter S. Beagle"

],

"isbns": [

"1616963085",

"9781616963088"

]

}

{

"title": "The Last Unicorn",

"authors": [

"Peter S. Beagle"

],

"isbns": [

"1616963182",

"9781616963187"

]

}Uh-oh. Why do we have so many distinct versions of The Last Unicorn? Well, each distinct format of a work has its own ISBN (so a hardcover, paperback, and eBook all have different ISBNs), even though the text may be identical. Then different editions (for example, a new foreword for a classic novel) all have their own set of unique ISBNs. Any given book may have dozens of ISBNs, each with their own unique entry in this API. That’s not going to work well for a search function: I just want to record that I read a book, not meticulously select which version of a book I read.

Works, not ISBNs

I was complaining about my situation to my partner; xe informed me that librarians think of this through the FRBR model. In short, there’s a distinction between the work (the book The Last Unicorn), the expression (a given edition of the book), a manifestation (a given physical format for an expression, such as paperback or hardcover), and an item (an individual object in a collection)[4].

I’m firmly working in the realm of the abstract, so items are irrelevant to me. Google Books’s API is giving back different expressions or manifestations (I’m not entirely clear on which), but we want works. How do we get our hands on those? There are some other book database options, most notably OpenLibrary, which have a model closer to what we want. Here’s the OpenLibrary work page for The Last Unicorn, for example. But the data’s still a little messy. Peek at the search results for Hotel Iris by Yoko Ogawa; the same work is duplicated four times. I’m still exploring ways to get data as clean as GoodReads or StoryGraph, but it turns out that there’s not a high-quality open-source database of books.

Letterboxd benefits from The Movie Database, which serves as its canonical source for films and film metadata. I would almost venture to describe Letterboxd as a commercialization of the commons, though the slick UI and social features are undeniably added value. If you want to build a similar book-focused project, it turns out that no analogue really exists. It could be a chicken-and-egg problem (I’m sure having a large, commercial service attached drives contributions to TMDB), but there’s also a difference of scale: there are around a million movies in the database today. Having played around with the data, I can say that OpenLibrary current has more than 40 million works in its (incomplete) catalogue. The problem is at least an order of magnitude harder and has much less money behind it.

Doesn’t mean I won’t try, though; look out for a potential future blogpost!

For a long time I thought I didn’t like movies; it turns out I actually just wasn’t watching ones to my taste! If you also think you don’t like movies, maybe ask a cinephile friend for some stuff to watch to try and triangulate your taste. ↩︎

I think the answer to my implicit question of “why is GoodReads clunky and unappealing?” is “it’s a low-priority offshoot of Amazon’s book-selling business.” ↩︎

As well as some desperately-unappealing selling points. I’m sure that there’s a target audience for computer-generated recommendations, AI-powered reading analytics, and user polls with questions like “is this book plot or character driven?” or “loveable characters?”. That audience isn’t me! ↩︎

Any errors in understanding are my own and not my partner’s. ↩︎